THE DOCTRINE OF INDOOR MANAGEMENT

THE DOCTRINE OF INDOOR MANAGEMENT

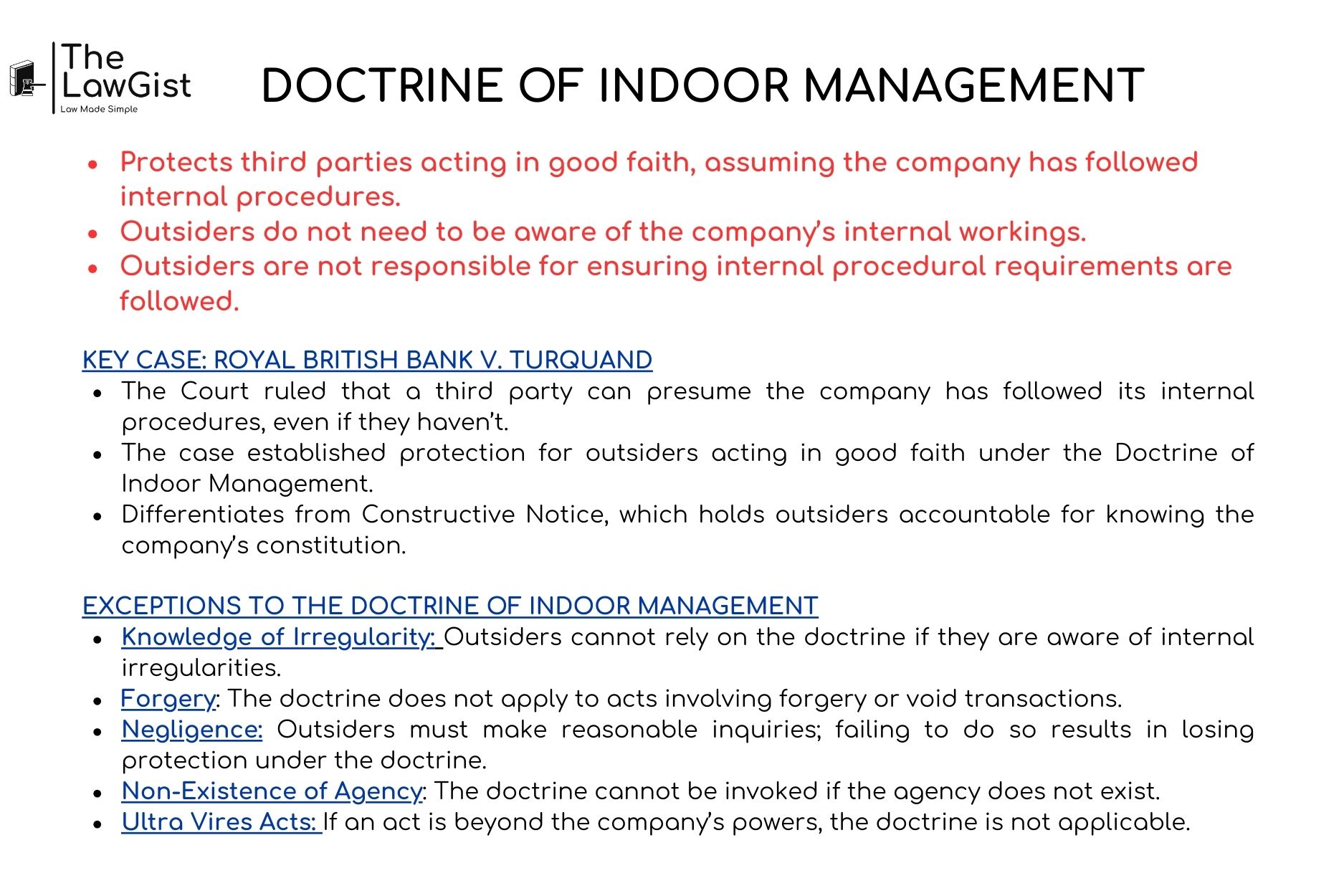

The Indoor Management Doctrine, also referred to as the Turquand Rule, originated from the British case Royal British Bank v. Turquand, which laid its foundation over a century ago. This doctrine protects third parties dealing in good faith with a company by shielding them from irregularities in the company’s internal proceedings.

Royal British Bank v. Turquand: Judgment

In Royal British Bank v. Turquand, the company’s articles of association allowed the directors to borrow money through bonds, but only if a resolution was passed at a general meeting to authorize such borrowing. Despite this requirement, the directors issued a bond to Turquand without obtaining the necessary resolution. The court ruled that Turquand could enforce the bond against the company, as he was entitled to presume that the required resolution had been properly passed.

The House of Lords established the principle that third parties dealing with a company in good faith can presume compliance with the company’s internal procedures, even if such compliance is absent. This principle, now known globally as the Doctrine of Indoor Management, shields third parties from the consequences of a company’s internal irregularities.

Sir John Jervis, representing the Exchequer Chamber, upheld the validity of the bond, stating that while the bank was aware of the directors’ borrowing powers as outlined in the articles of association, it was not obligated to ensure that the necessary internal procedures had been followed. Since the bond bore the signatures of two directors and the company seal, the company was deemed liable for the repayment.

Lord Hatherly also observed: “Outsiders are bound to know the external position of the company but are not bound to know its indoor management.” This judgment reinforced that companies cannot evade their obligations to third parties by relying on failures in their internal governance.

Factual Example

Ravi and Phani entered into a contract with a company named Pantans to purchase a large consignment of clothing. According to Pantans’ Articles of Association, its directors could authorize such transactions only after obtaining approval through a resolution passed in a general meeting.

The contract for the clothing purchase was executed by two directors of Pantans and was affixed with the company’s seal.Ravi and Phani, acting in good faith, assumed that all necessary internal approvals had been obtained. However, it later came to light that no such resolution had been passed, and Pantans attempted to void the contract, claiming that the internal procedure required for authorizing the transaction had not been followed.

Applying the Doctrine of Indoor Management, Ravi and Phani would be protected. As third parties, they were entitled to presume that the internal procedures of Pantans had been properly carried out. Pantans cannot rely on its internal irregularities to avoid its contractual obligations. Consequently, the company remains bound by the contract and must honor its terms.

This illustrates how the doctrine safeguards outsiders like Ravi and Phani from being adversely affected by internal lapses within a company.

Exceptions to the Doctrine of Indoor Management

- Knowledge of Irregularity: The doctrine does not apply if the outsider is aware, either directly or indirectly, of any irregularities. For example, in Howard v. Patent Ivory Co., a director who was aware that the borrowing limits had been surpassed could only claim the amount that was authorized by the company.

- Ignorance of Memorandum and Articles: If the outsider fails to consult the company’s memorandum and articles, they cannot invoke the doctrine. In Rama Corporation v. Proved Tin & General Investment Co., the plaintiffs could not claim protection as they did not know the articles allowed delegation of authority.

- Forgery: The rule does not cover transactions involving forgery, as no consent exists. In Rouben v. Great Fingal Consolidated, share certificates issued with forged signatures were deemed invalid.

- Negligence: The doctrine does not protect those who fail to make reasonable inquiries. In Underwood v. Bank of Liverpool, a bank was held liable for not verifying a director’s authority when he deposited company cheques into his personal account.

- Non-Existence of Agency: The doctrine does not apply if the question concerns the very existence of an agency

- Ultra Vires Acts: If a company’s act is beyond its powers (ultra vires), the doctrine does not apply, as in Pacific Coast Coal Mines v. Arbuthnot.

Additionally, Section 6 of the Companies Act, 2013, invalidates any provision in the memorandum, articles, agreements, or resolutions that conflict with the Act.

ARTICLE WRITTEN BY – Gaddam Sneha Deepthi

EDITOR – Nancy Sharma